WHY YOU DIDN’T GET CAST

A few days ago, I had two conversations almost back-to-back. One was with an experienced and talented actor who believed they were getting the message that their career was over just because they were in a dry spell. The other was with yet another Bay Area actor whose career had stalled the minute they went AEA. While we talked about the many reasons why that happens, this actor said to me, “I want to see if I’m good enough to be an AEA actor.” And my heart just broke because, as someone whose life is always on the other side of the table, I know how seldom casting is purely about who’s “good.” I hate that experienced, talented actors can see whether or not they get cast as a measure of their intrinsic worth as actors.

So here you go, actors of the world. The pure, unvarnished truth about why you didn’t get the role.

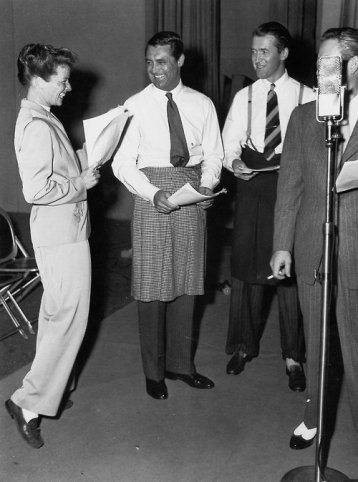

Katherine Hepburn, Cary Grant, and Jimmy Stewart performing Philadelphia Story for Victory Theater, 1942.

1. MOST COMMON: You’re just not right for it. I know this sounds like a massive, shit-eating cliche, but it’s absolutely the truth. A director walks into the room with a character conceptualized in a certain way, and is looking for the person whose type or energy matches the character. The truly amazingly badass Leslie Martinson of TheatreWorks taught me this years ago, when I was first starting out: Every conceptualized character has thirteen adjectives that describe them. Every actor has thirteen adjectives that describe them. Casting is about finding the best match. I pass over actors I flat-out adore all the time because the fit isn’t right. For example, a director might have Orlando conceptualized as a man in his 20s with a gentle, soft-spoken energy, while your audition presents a man in his 30s with a bright, aggressive energy. While your audition might be fantastic, you’re not going to be that director’s Orlando.

3. The role was precast. Some directors are superstitious and will read people for roles that are already cast. It’s unfortunately common for actors to commit to roles that they later bail on (a better-paying gig, a family emergency, a medical situation), and if you auditioned other actors for that role, you have some go-to options. One casting director told me she was so superstitious that she didn’t get rid of the casting data for a show until it CLOSED. On the flip side, lots of theatres are upfront about which roles are precast. Don’t let that necessarily discourage you. You may want to consider coming in for a show where your dream role is precast– you may end up playing that role after all.

4. The role went to someone they’ve worked with before. This is incredibly common. You know an actor’s work, you have a shared language, you understand how to work together. A known quantity is less of a risk, even if the known quantity didn’t crush the callback like you did. The director knows from past experience that the other actor can give them what the work needs.

5. You’ve had a history of behaving unprofessionally. Luckily, this one is extremely rare, but it does occasionally happen. Violating your contract (coming consistently late or no-showing to rehearsals or shows, for example), treating fellow actors or crew disrespectfully, making unreasonable demands (such as demanding the theatre violate their contract with the playwright so you can change something in the script despite the fact that the playwright declined to allow the change, or demanding the day off during tech because it’s your one year dating anniversary), deciding closing night is the time for GAGS! and IMPROV!, badmouthing the show on social media (“This play is going to be total shit!”). Although I’ve seen every one of these examples firsthand, they are, as I’ve said, pretty rare. The converse, happily, is MUCH more likely to be true– that we take a chance on an actor unknown to us because someone at another theatre is raving about how awesome they are. And believe me, I’m not trying to imply that this doesn’t happen in the opposite direction. I know plenty of directors treat actors in unconscionable ways. But that’s an entirely different blog post. My point is that, in any theatre community, companies share personnel. While we don’t necessarily go out of our way to share that kind of information, the Literary Manager at one theatre is directing a show at another theatre. The actor at one theatre is the Artistic Director at another theatre. What happens in Vegas, so to speak, does not stay in Vegas. But be happy that the converse is also true and much, much more common– we’re raving about how wonderful you are to our friends at other companies. I’ve sent many a “heads up” email to directors to let them know that an actor new to them and about to audition for them is someone I’ve worked with and believe in.

6. Conflicts. You may have been the best person for the role, but since you’re planning to be in Oklahoma for Baton Twirling Nationals during tech, they’re going to go with someone else.

7. You tanked the audition. Oh, man, this one is a heartbreaker, and I see it all the time. It’s one of the reasons I tell my students that the best way to cast is to see as many plays as possible so you’re seeing actors in their natural habitat. Auditions are weird little creatures, artificial and forced. However, if we want to open our theatres to new people and new communities (and we do), we’re stuck with open auditions. Like standardized testing, which only measures how good you are at standardized tests, auditions often measure how well you audition and little else. While callbacks are theoretically meant to correct for that, you don’t always make it to the callback to show them. I’ve seen plenty of actors give me a crap audition and then give a beautiful performance in someone else’s play. They had a bad day, or memorized a new monologue they thought would be “better” for the role the day before, or were too nervous.

There are a million reasons why a great actor would tank an audition. Don’t let it discourage you. Take an audition class or work with a coach if this is a common problem for you. Do what you need to do. But KEEP TRYING. Invite artistic directors and casting directors to see your work. Don’t give up! You won’t tank them all.

And that’s my main piece of advice: Don’t give up. If this is your dream, persevere! Nothing is insurmountable. FALL DOWN SEVEN TIMES, GET UP EIGHT.

No comments:

Post a Comment